The Imperial Airship Scheme

The plans for the R.101 were laid down as far back as 1924 when the Imperial Airship Scheme was proposed. The requirements included that a ship was proposed to take some 200 troops for the military or 5 fighter craft as an aerial aircraft carrier. It was noted that a larger ship of some 8 million cubic feet would be required; however, for initial plans, two prototype ships of 5 million cft were to be constructed.

It was decided that to promote innovation, one ship would be contracted out to a private company and the other would be built at the Royal Airship Works in Cardington. The first ship, the R100, was built by a subsidiary of Vickers, the Airship Guarantee Company, at the shed at Howden in Yorkshire.

The second prototype ship, the R.101, again moved away from traditional lines of design. After some delays with the initial project, the scheme soon got underway when work on the ship began in 1926.

R.101 Design

The ship was to have many innovative design features, and incorporating these within the ship was to cause some delay to the original completion date of 1927. However, it must be remembered that this project was the largest of its kind ever undertaken in the world at that time. The previous largest ship was the Graf Zeppelin, and that was based on the original design of the “LZ126” Los Angeles, a much smaller ship than was being constructed in Britain.

The whole airship programme was under the direction of the Director of Airship Development (DAD), Group Captain Peregrine Fellowes, with Colmore acting as his deputy. Lieutenant-Colonel Richmond was appointed Director of Design: later he was credited as “Assistant Director of Airship Development (Technical) with Squadron Leader Michael Rope as his assistant, and the Director for Flying and Training, responsible for all operational matters for both airships, was Major G.H. Scott, who had developed the design of the mooring masts that were to be built.

R.101 was to be built only after an extensive research and test programme was complete. This was carried out by the National Physical Laboratory (NPL). As part of this programme, the Air Ministry funded the costs of refurbishing and flying R33 in order to gather data about structural loads and the airflow around a large airship. This data was also made available to Vickers; both airships had the same elongated tear-drop shape, unlike previous airship designs. Hilda Lyon, who was responsible for the aerodynamic development, found that this shape produced the minimum amount of drag. Safety was a primary concern, and this would have an important influence on the choice of engines.

An early decision had been made to construct the primary structure largely from stainless steel rather than lightweight alloys such as duralumin. The design of the primary structure was shared between Cardington and the aircraft manufacturer Boulton and Paul, who had extensive experience in the use of steel and had developed innovative techniques for forming steel strip into structural sections. Working to an outline design prepared with the help of data supplied by the NPL, the stress calculations were performed by Cardington.

This information was then supplied to J. D. North and his team at Boulton and Paul, who designed the actual metalwork. The individual girders were fabricated by Boulton and Paul in Norwich and transported to Cardington, where they were bolted together. This scheme for a prefabricated structure entailed demanding manufacturing tolerances and was entirely successful, as the ease with which R.101 was eventually extended bears witness.

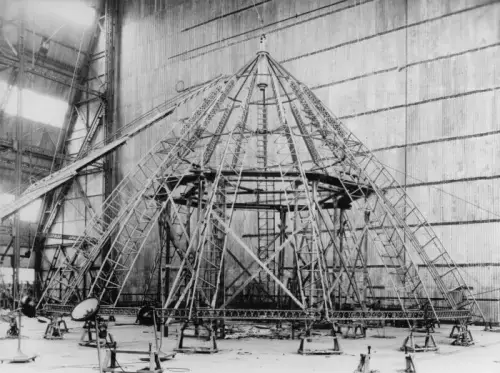

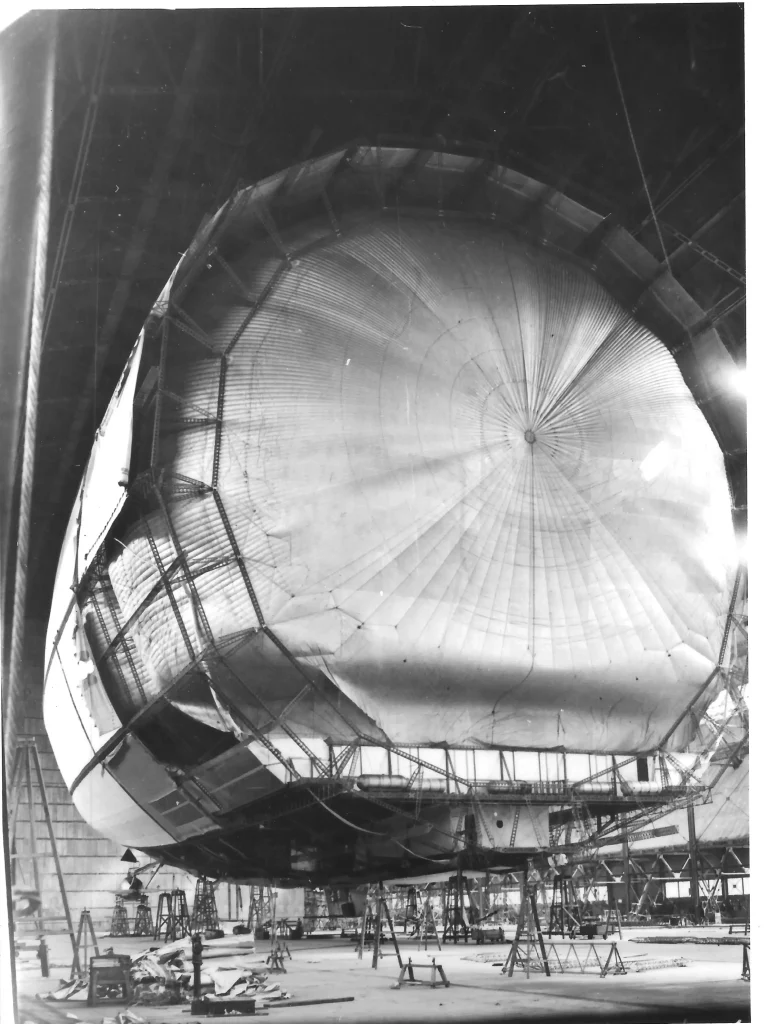

Before any contracts for the metalwork were signed, an entire bay consisting of a pair of the 15-sided transverse ring frames and the connecting longitudinal girders was assembled at Cardington. After the assembly had passed loading tests, the individual girders were then tested to destruction. The structure of the airframe was innovative: the ring-shaped transverse frames of previous airships had been braced by radial wires meeting at a central hub, but no such bracing was used in R.101, the frames being stiff enough in themselves. However, this resulted in the structure extending further into the envelope, thereby limiting the size of the gasbags.

The specifications drawn up in 1924 by the Committee for the Safety of Airships were based on weight estimates on the then-existing rules for airframe strengths. However, the Air Ministry Inspectorate introduced a new set of rules for airship safety standards in late 1924, and compliance with these as-yet unformulated rules had been explicitly mentioned in the individual specifications for each airship.

These new rules called for all lifting loads to be transmitted directly to the transverse frames rather than being taken via the longitudinal girders. The intention behind this ruling was to enable the stressing of the framework to be fully calculated, rather than relying on empirically accumulated data, as was contemporary practice at the Zeppelin design office. Apart from the implications for the airframe weight, one effect of these regulations was to force both teams to contrive a new system of harnessing the gasbags.

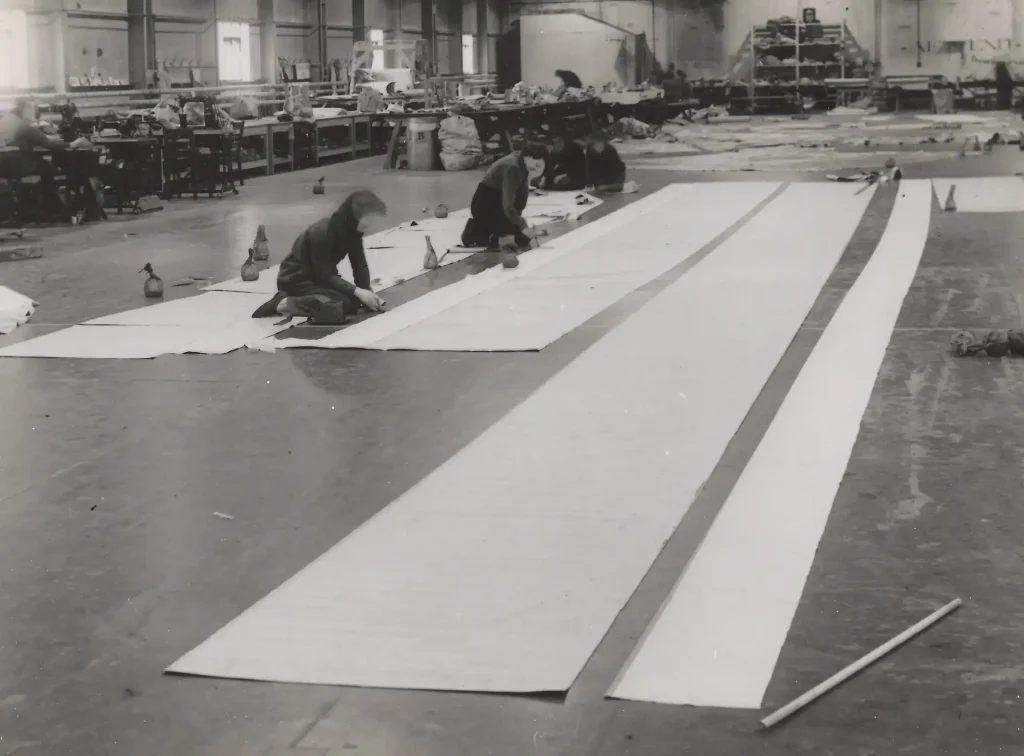

R.101 used pre-doped linen panels for much of its covering, rather than lacing undoped fabric into place and then applying dope to shrink it. In order to reduce the area of unsupported fabric in the covering, R.101 alternated the main longitudinals with non-structural “reefing booms” mounted on kingposts which were adjustable using screw-jacks in order to tension the covering.

There were other innovative design features. Previously, ballast containers had been made in the form of leather ballast bags, which looked like a pair of large leather “trousers”, and one or other leg could be opened at the bottom by a cable release from the control car. In R.101, the extreme forward and aft ballast bags were of this type and were locally operated, but the main ballast was held in tanks connected by pipes so that ballast could be transferred from one to another to alter the airship’s trim using compressed air.

The arrangement for ventilating the interior of the envelope, necessary both to prevent any build-up of escaped hydrogen and also to equalise pressure between the outside and inside, was also innovative. A series of flap-valves were situated at the nose and stern of the airship cover (those at the nose are clearly visible in photographs) to allow air to enter when the airship was descending, while a series of vents was arranged around the circumference amidships to allow air to exit during ascent.

Engines

Heavy oil (diesel) engines were specified by the Air Ministry because the airship was intended for use on the India route, where it was thought that high temperatures would make petrol an unacceptable fire hazard because of its low flash point. A petrol explosion had been a major cause of fatalities in the loss of the R38 in 1921.

Initial calculations were based on the use of seven Beardmore Typhoon six-cylinder heavy-oil engines, which were expected to weigh 2,200 lb (1,000 kg) and deliver 600 bhp (450 kW) each. When the development of this engine proved impractical, the use of the eight-cylinder Beardmore Tornado was proposed instead. This was an engine being developed by Beardmore by combining two four-cylinder engines, which had originally been developed for railway use.

In March 1925, these were expected to weigh 3,200 pounds (1,500 kg) and deliver 700 bhp (520 kW) each. Because of the increased weight of each engine, it was decided to use five, resulting in overall power being reduced from 4,200 bhp (3,100 kW) to 3,500 bhp (2,600 kW).

Unexpectedly, severe torsional resonance of the crankshaft was encountered above 950 rpm, limiting the engine to a maximum of 935 rpm, giving an output of only 650 bhp (485 kW) with a continuous power rating at 890 rpm of 585 bhp (436 kW). The engine was also considerably above estimated weight, at 4,773 lb (2,165 kg), over double the initial estimate.[28] Some of this excess weight was the result of the failure to manufacture a satisfactory lightweight aluminium crankcase.

The original intention had been to fit two of the engines with variable-pitch propellers in order to provide reverse thrust for manoeuvring during docking. The torsional resonance also caused the hollow metal blades of these reversing propellers to develop cracks near the hubs, and as a short-term measure, one of the engines was fitted with a fixed-pitch reverse propeller, consequently becoming dead weight under normal flight conditions. For the airship’s final fligh,t two of the engines were adapted to be capable of running in reverse by a simple modification of the camshaft.

Each engine car also contained a 40 bhp (30 kW) Ricardo petrol engine for use as a starter motor. Three of these also drove generators to provide electricity when the airship was at rest or flying at low speeds: at normal flight speeds the generators were driven by constant-speed variable-pitch windmills. The other two auxiliary engines drove compressors for the compressed air fuel and ballast transfer system. Before the final flight one of the petrol engines was replaced by a Beverly heavy oil engine. In order to lessen the risk of fire, the petrol tanks could be jettisoned.

Diesel fuel was contained in tanks in the transverse frames, the majority of the tanks having a capacity of 224 imp gal (1,018 l). A mechanism was provided for dumping fuel directly from the tanks in an emergency. By the use of tankage provided for weight compensation when travelling with a light passenger load, a total fuel load of 10,000 imp gal (45,000 l) could be carried.

Crewing and control

In normal service, the R.101 carried a crew of 42. This consisted of two watches of 13 men under the officer of the watch, this duty being divided among the three principal ship’s officers.

In addition there were the chief navigator, the meteorological officer, the chief coxswain, the chief engineer, the chief wireless officer and the chief steward, who were not assigned to watches but were on duty as necessary, and four supernumeraries (three engineers and a radio operator) who were available to provide relief watch keeping if necessary, and an assistant steward, a cook and a galley boy who were on duty as required between 06:30 and 21:30.

The minimum crew requirement, as specified in the airship’s Certificate of Airworthiness, was 15 men.

The control car was occupied by the duty officer of the watch and the steering and altitude coxswains, who respectively controlled the rudder and elevators using wheels similar to a ship’s wheel. The engines were individually controlled by an engineer in each of the engine cars, orders being given by an individual telegraph to each car. These moved an indicator in the engine car to signal the desired throttle setting and also rang a bell to draw attention to the fact that an order had been transmitted.

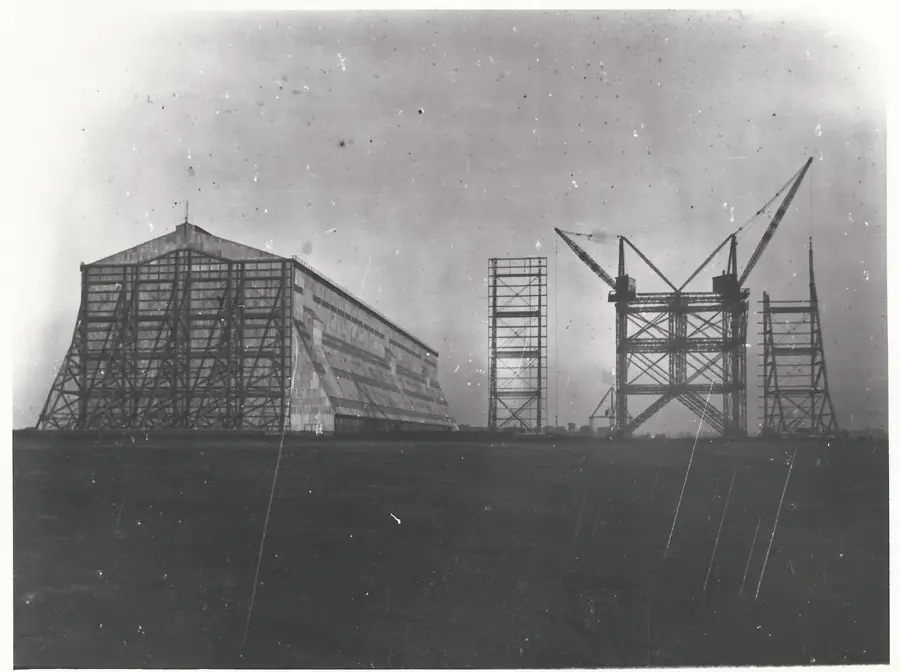

With the agreement and funding made for the Imperial Airship Scheme, it was noted that the original shed was too small for the designed R.101, and so had to be lengthened and also raised in height.

Shed Changes

Work was started in October 1924 on the lengthening and raising of Shed 1, which was completed in May 1926. A second shed was also required, and so it was agreed that shed 2 from the Pulham operational base would be used. This was dismantled in June 1927 and re-erected next to Shed 1. The second shed was completed in 1928. In that time, the R.101 was slowly being assembled in shed 1 next door. Shed 2 was going to house the R100, which was being built in the airship construction facility in Howden, Yorkshire. The delay in dismantling the Pulham shed was due to very bad weather at the time.

Construction

The framework and girders were subcontracted out and made by Boulton and Paul in Norwich at the beginning of January 1927. These were then driven to Cardington on the back of a lorry, or sent by railway wagon for the larger items. Hundreds of these smaller girders were assembled on the floor of the shed to make the rings, then winched up and connected up like a giant Meccano set. The R.101 would eventually contain over 30,000 ft of girder work on the R.101.

Work on the rings at Cardington started in December 1927, and rings 4-11 were completed by July 1928.

The engineers and designers were based at Cardington, and the “Administration” block was where the design offices were. There were some 270 people involved in the design and drawing offices, and some 700 people on the construction side, split between Cardington and Boulton and Paul, in Norwich.

The huge airship mast was constructed for the civil programme in 1926, built by the Cleveland Bridge and Engineering Company under the direction of Major General Sir William Liddell, Director of Works and Buildings at the Air Ministry. 202 feet high and 70 feet in diameter at the base, the tower was the first ever cantilever mooring mast to be built.

Inflation

The lengthy process of inflating the R.101’s hydrogen gasbags began on 11 July 1929 and was complete by 21 September. With the airship now airborne and loosely tethered within the shed, it was now possible to carry out lift and trim trials. These were disappointing. A design conference held on 17 June 1929 had estimated a gross lift of 151.8 tons and a total airframe weight, including the power installation, of 105 tons.

The actual figures proved to be a gross lift of 148.46 tons and a weight of 113.6 tons. Moreover, the airship was tail-heavy, a result of the tail surfaces being considerably above estimated weight. In this form, a flight to India was out of the question. Airship operations under tropical conditions were made more difficult by the loss of lift in high air temperatures: the loss of lift in Karachi was estimated to be as much as 11 tons for an airship the size of R.101.

Emerging from the Shed

On 2 October, the press were invited to Cardington to view the finished airship. However, weather conditions made it impossible to take it out of the shed until 12 October, when it was walked out by a ground-handling party of 400.

The event attracted a huge number of spectators, with surrounding roads a solid line of cars.

The moored airship continued to attract spectators, and it was estimated that more than a million people had made the trip to Cardington to see R.101 at the mast by the end of November.

1929 – The First Trial Flights (Flights 1-7)

– photo copyright Roger Davis, taken by his father in Enfield, London

R.101 made its first flight on 14 October. After a short circuit over Bedford, the course was set for London, where it passed over the Palace of Westminster, St Paul’s Cathedral and the City, returning to Cardington after a flight lasting five hours 40 minutes. During this flight, the servos were not used, without any difficulty being experienced in controlling the airship.

A second flight lasting nine hours 38 minutes followed on 18 October, with Lord Thomson among the passengers, after which R.101 was briefly returned to the shed to enable some modifications to be made to the starting engines.

A third flight lasting seven hours 15 minutes was made on 1 November, during which it was flown at full power for the first time, recording a speed of 68.5 mph (110.2 km/h): even at full speed, it was not found necessary to use the control servos. During this flight, it paid a visit to the Boulton and Paul works near Nottingham and also circled over Sandringham House, observed by the King and Queen.

On 2 November, the first night flight was made, slipping the mast at 20:12 before heading south to fly over London and Portsmouth before attempting a speed trial over a 43 mi (69 km) circuit over the Solent and the Isle of Wight. These trials were frustrated by pipe breakages in the cooling systems of two of the engines, a problem later solved by replacing the aluminium piping with copper. It returned to Cardington around 09:00, the mooring operation ending in a minor accident, damaging one of the reefing booms at the bow.

On 8 November, a short flight purely for public relations purposes was made, carrying 40 passengers, including the Mayor of Bedford and various officials. To accommodate this load, the airship was flown with only a partial fuel and ballast load and was inflated to a pressure height of 500 ft (150 m).

Two days later, the wind began to rise, and gales were forecast. On 11 November, the wind touched 83 mph (134 km/h), with a maximum gust speed of 89 mph (143 km/h). Although the ship’s behaviour at the mast gave cause for a good deal of satisfaction, there was nevertheless some cause for concern. The movement of the ship had caused considerable movement of the gasbags, the surging being described by Coxswain “Sky” Hunt as being around four inches (ten cm) from side to side and “considerably more” longitudinally. This caused the gasbags to foul the framework, and the resulting chafing caused the gasbags to be holed in many places.

A sixth flight was made on 14 November to test the modifications that had been made to the cooling system and the repairs to the gasbags, carrying a load of 32 passengers, including 10 MPs with a special interest in aviation and a party of air ministry officials headed by Sir Sefton Brancker, the Director of Civil Aviation.

On 16 November, it had been planned to carry out a demonstration flight for a party of 100 MPs, a scheme that had been suggested by Thomson in the expectation that few would wish to take advantage of the offer; in the event, it was oversubscribed. The weather on the day was unfavourable, and the flight was rescheduled. The weather then cleared, and on the following day, R.101 slipped the mast at 10:33 to carry out an endurance trial, planned to last at least thirty hours.

R.101 passed over York and Durham before crossing the coast and flying over the North Sea as far north as Edinburgh, where it turned west towards Glasgow. During the night, a series of turning trials were made over the Irish Sea, after which the airship was flown south to fly over Dublin (the home town of R.101’s Captain, Carmichael Irwin) before returning to Cardington via Anglesey and Chester.

After some delay in finding Cardington owing to fog, R.101 was secured to the mast at 17:14, after a flight lasting 30 hours 41 minutes. The only technical problem encountered during the flight was with the pump for transferring fuel, which broke down several times, although subsequent examination of the engines showed that one was on the point of suffering a failure of a big-end bearing.

The flight for the MPs had been rescheduled for 23 November. With the barometric pressure low, R.101 lacked sufficient lift to carry 100 passengers, even though all but a bare minimum of fuel was drained off and the ship was lightened by removing all unnecessary stores.

The flight was cancelled because of the weather, but not before the politicians had arrived at Cardington: they accordingly embarked and had lunch while the ship rode at the mast, only kept in the air by dynamic lift produced by the 45 mph (72 km/h) wind. Following this, R.101 remained at the mast until 30 November, when the wind had dropped enough for it to be walked back into the shed.

While the initial flight trials were being carried out, the design team examined the lift problem. Studies identified possible weight savings of 3.16 tons. The weight-saving measures included deleting twelve of the double-berth cabins, removing the reefing booms from the nose to frame 1 and between frames 13 to 15 at the tail, replacing the glass windows of the observation decks with Cellon, removing two water ballast tanks, and removing the servo mechanism for the rudder and elevators. Letting the gasbags out would gain 3.18 tons extra lift.

Since there were thousands of exposed fixings protruding from the girders, chafing of the gasbags would have to be prevented by wrapping these in strips of cloth.

After more trials, it was decided that more drastic action would be required to enhance the overall lift of the airship. During the winter of 1929 to 1930, the airship was brought into the shed, and the re-wiring of the gasbag bracing could commence, and obtain extra lift. The R.101 was put in the shed from 30th Nov 1929 – 23rd June 1930

On a visit to Cardington in the Graf Zeppelin, Hugo Eckener was given a tour of the new ship and agreed that the R.101 heralded a new breed of exceptional ship. There was confidence in this new prototype, which would lead to bigger ships, as planned in the R102 and R103.

Original HMA R.101 Schedule to Karachi

| Outward | Times (approx. due to local conditions) | . |

| Depart Cardington | Midnight 26th September | . |

| Arrive Ismalia | after Sunset 28th September | (refuel) |

| Depart Ismalia | Before Sunrise 1st October | . |

| Arrive Karachi | before Sunrise 1st October | (refuel) |

| Return | Times (approx. due to local conditions) | . |

| Depart Karachi | After Sunset 5th October | . |

| Arrive Ismalia | After Sunset 8th October | (refuel) |

| Depart Ismalia | Before Sunrise 9th October | . |

| Arrive Cardington | After Sunset 11th October | (refuel) |

Duration: 15 days round tripOutward: 5 days

Stop Over: 4 days

Return: 6 Days

By comparison, the existing Imperial Airways service took 8 days one way and had 21 stops en route. By liner, the quickest sea route took 4 weeks.

In 1930 a passenger was so confident in the proposed service that he had sent the Royal Airship Works £20,000 for one airship passage to New York in 1931. It was thought that the two ships could earn useful revenue over 1931-1932 with commercial operations.

Even though the R.101 was often said to be flying too low compared to the earlier Zeppelins, which had reached some 20,000 feet altitude during the war, it was advised that all commercial (non military airships) had to fly long range and to do this had to fly at a low level, hence the ships were designed for this.

The best economic results were if a ship could maintain a height of 1,500feet. This was not only financially advantageous but would also “afford splendid views of the ground and sea”. The Zeppelin Company had to adopt this policy with the LZ129 – Hindenburg, which would keep between 1,500 and 4,000 feet.

Life on Board

The R.101 was seen as a lavish floating hotel. Even by today’s standards, the open promenades and public spaces would be seen as unique in the skies.

These large British ships were the first to adopt the style of using the interior of the ship for passenger accommodation. The only contemporary ship which was running a passenger service was the German Zeppelin ZL127 – Graf Zeppelin.

Even then, the ship could only accommodate 20 passengers who were situated in a stretched forward gondola beneath the hull of the ship. The utilisation of interior space within the R100 and R. R101 was a first of its kind, and the R. R101 could boast 2 decks of space, a dining room which could seat 60 people at a time and a smoking room which could seat 20. The promenades showed off the view to the fullest advantage.

Compared to the noisy, smelly and tiring journey in an aeroplane, the airships were seen as pure luxury, with service comparable to that of the greatest ocean liners.

The Main Lounge

The colour scheme was white panels with gold inlay. The curtains on the promenade deck were of fine Cambridge blue. The seating arrangements were of small tables, and the chairs were constructed of upholstered cane wicker. At each side of the left side of the lounge were writing desks running alongside the wall. The ship had provided R101 headed stationery. On the walls were paintings; however, we have not been able to ascertain what they depicted at the present time.

Either side of the lounge was the Promenade deck, where three steps led up to the deck. The curtains would be drawn closed at night in order to give those on the Promenade Deck a better view of the ground without light pollution from the lounge. The cushions on the side chairs were inflated with air to save weight.

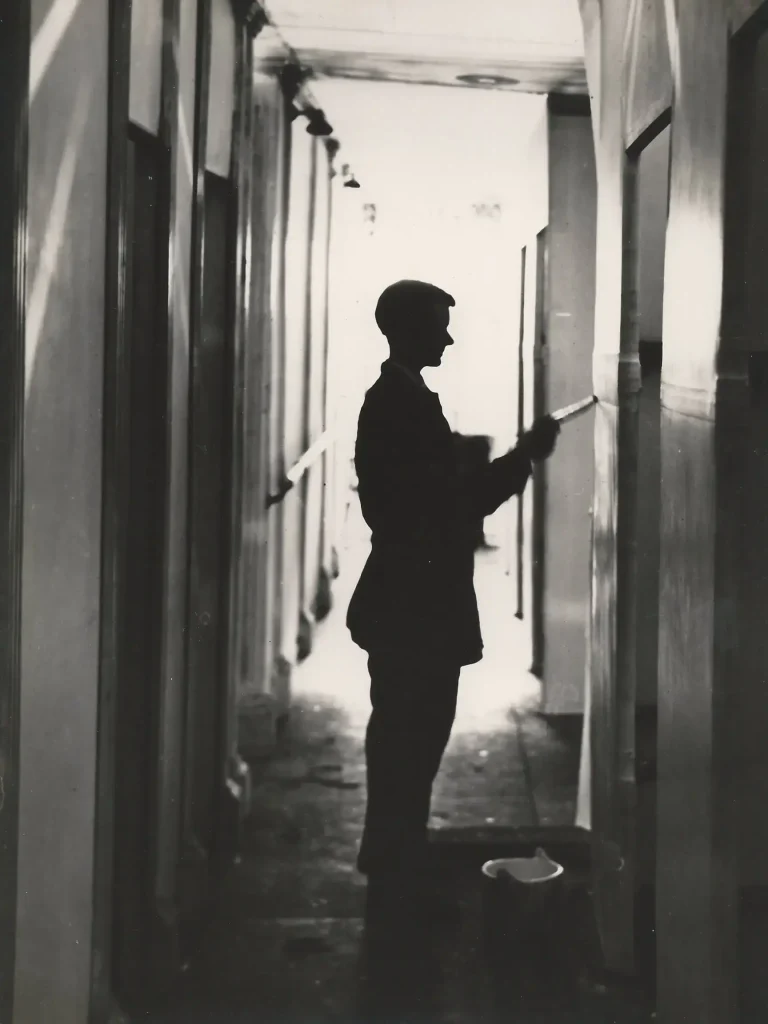

The Promenade Decks

The promenade decks had deck chairs and a safety rail with a footrest. The design followed very traditional nautical designs and almost felt as if passengers were on the deck of a ship. Deck chairs were provided for seated viewing.

The promenade decks were on both sides of the lounge and also ran along the side of the dining room. Even though early designs suggested that they would both be interlinked, there was no door between each section of the promenade decks.

The original windows were made of glass but were removed and replaced by lightweight cellulose safety glass.

A second set of windows and promenade ran along the corridor on the starboard side of the passenger accommodation near the sleeping quarters.

The promenade decks had deck chairs and a safety rail with a footrest. The design followed very traditional nautical designs and almost felt as if passengers were on the deck of a ship. Deck chairs were provided as seen here.

The promenade decks were on both sides of the lounge and also ran along the side of the dining room. Even though early designs suggested that they would both be interlinked, there was no door between each section of the promenade decks.

The original windows were made of glass but were removed and replaced by lightweight cellulose safety glass.

A second set of windows and promenade ran along the corridor on the starboard side of the passenger accommodation near the sleeping quarters.

A second set of windows provided light to the corridor on the starboard side of the ship and the passenger cabins. This promenade was opposite to the port side of the ship where the dining room was, and also had a similar window/railing layout.

These windows were removed in September 1930 as part of the weight-saving programme. Few photographs of the ship exist with the second set of windows removed.

Passenger Cabins

The sleeping arrangements were in the form of bunks. Even though they may seem spartan, the cabins were warmed by a heating vent driven from the main radiator, which could be heated or cooled by being lowered out of the ship.

Each cabin had a main “porthole” electric light, fitted to the wall with a small blind which could be drawn over it. This continued the nautical influence. A small reading light was also provided above each bunk.

A small luggage stool would be provided for cabin bags, and a small rug would be on the floor. Each cabin had a notice regarding the protocols of airship life, including details for summoning a steward.

Some 50 cabins were constructed in formations of single, twin and four-berth arrangements.

Washroom facilities were available close by. These had aluminium sinks with long half-length mirrors suspended on two wires in front of the basins.

Toilets were on the lower deck.

Meal Times and Dining

All meals for passengers and Officers were to be taken in the Dining room, which could seat up to 60 people. It was not known what would have been eaten en route, but a recent discovery of an R.101 Menu (unfortunately undated) and a wine list from 6th November 1929. It is suspected that the menu was from the visit by 50 MPs on November 23rd 1929. It gives an idea of the menu available. It is also interesting to note that the “smoking room” is referred to as the “smoke room”

| Passengers and Officers | Time | Crew Meal Times | Time | |

| Breakfast | 07.30am – 09.30am | Breakfast | 07.20am – 08.30 am | |

| Lunch | 11.30am – 13.00pm | Lunch | 11.20am – 12.30 pm | |

| Afternoon Tea | 15.30pm – 16.30pm | Tea | 15.30pm – 16.30 pm | |

| Dinner | 19.30pm – 20.30pm | Supper | 19.30pm – 20.30 pm |

Below Decks – Crew’s Quarters

The crew’s sleeping quarters were in the lower deck of the ship. The crew had a series of sets of sleeping accommodations and as seen here, were comfortable compared to those of the Zeppelins, in which it was not uncommon for the crew to sleep in hammocks. The R101 crew had a large mess hall for their private space. This contained a large table with bench seating.

The lower deck also contained the cargo hold into which the luggage and stores could be hoisted through the cargo hatch using the winch.

The Galley

All of the utensils were made of light aluminium. The galley was well fitted out with an all-electric oven, a vegetable steamer and ample space for the chef.

The Smoking Room

A unique example of design. The R101 was fitted with a smoking room on the lower deck able to seat 24 people. The floor and ceiling were made of light asbestos with a thin sheet of metal on the floor. The walls were metal-covered cloth. The smoking room was not considered a hazard to the ship, as all precautions had been taken with materials in construction. This is where you could retire after dinner and enjoy a cigar and a postprandial drink.

Lower Deck Corridor

The corridor from the nose of the ship to the passenger accommodation was constructed of a similar material to the corridors above in the upper deck. This meant that the passengers entering the ship would see a long white and gold “panelled” corridor to the lower deck accommodation and a stair case up to the main cabins. The corridor had wooden doors on each side to the crew’s quarters, the cargo room, the wireless room, the galley, the smoking room and the toilets.

There were small windows in the lower deck corridor near the wireless room and the chart room. Lower windows were also in the crew room.

Baggage/ Cargo

Even though weight was the biggest issue with airships, crew and passengers could take up to 30lbs of kit/baggage as an allowance. On the R.101’s final flight, the baggage and kit of some 54 people had an average weight of baggage per person of 22lbs. Some of the items included:

- Cask of Ale – 70lbs

- Carpet Roll – 129lbs (flown over for the state dinners at Karachi and Ismalia)

- Two cases of Champagne – 52lbs.

Crew Watch Times

Airships were run along the lines of maritime service, with ship watches set on similar lines to their naval partners. The watches were split in duration as 4 hours for a “day” watch and reduced to 3 hours for a “night” watch:

| Watch Name | Time |

| Forenoon Watch | 08.00am – 12.00pm |

| Afternoon Watch | 12.00pm – 16.00pm |

| Evening (Dog) Watch | 16.00pm – 20.00pm |

| 1st Night Watch | 20.00pm – 23.00pm |

| Middle Watch | 23.00pm – 02.00am |

| 1st Morning Watch | 02.00am – 05.00am |

| 2nd Morning Watch | 05.00am – 08.00am |

1929 -1930 More Lift Needed – further refit

Over the summer of 1930, the R.101 lay in the Number 1 shed at Cardington undergoing extensive modifications, which were needed following on from her 1929 and early 1930 trial flights.

It was already known that both the R100 and R.101 were lacking in the disposable lift originally planned at the outset of the Imperial Airship Scheme in 1925. Those involved in the scheme had already learnt that the R100 and R.101 would not be viable for full commercial operations to Canada and India, and these intentions were later to be passed on to the new ship, the R102 class.

1930 – Further Trial flights (8-10)

On the morning of 23 June, when R.101 was walked out of the shed. It had been at the mast for less than an hour in a moderate wind when an alarming rippling movement was observed, and shortly afterwards, a 140 ft (43 m) tear appeared on the right-hand side of the airship. It was decided to repair these at the mast and to add more strengthening bands. This was done by the end of the day, but the next day, a second, shorter split occurred. This was dealt with in the same way, and it was decided that if the reinforcing bands were added to the repaired area, the scheduled appearance at the RAF pageant at Hendon could be made.

R.101 made three flights in June, totalling 29 hours 34 minutes duration. On 26 June, a short proving flight was made, the controls, no longer servo-operated, being described as “powerful and fully adequate”. At the end of this flight, the R.101 was found to be “flying heavy” and two tons of fuel oil had to be jettisoned in order to lighten the airship for mooring. This was initially attributed to changes in air temperature during the flight.

On the following two days, R.101 made two flights, the first to take part in the rehearsal for the RAF display at Hendon and the second to take place in the display itself. These flights revealed a problem with lift, considerable jettisoning of ballast being necessary. An inspection of the gasbags revealed a large number of holes, a result of the letting out of the gasbags, which allowed them to foul projections on the girders of the framework

To achieve the additional lift, R.101 it was agreed that a new central bay and gas bag would be installed. The R.101 entered shed number one on 29th June

It was expected that the new bay and extra gas bag would give her another nine tons of disposable lift, bringing her up to some 50 tons. The alterations were completed by Friday, the 26th September and the R.101 was gassed up and floated in the shed.

The “new” ship, R.101c, had a disposable lift calculated at 49.36 tons, an improvement of 14.5 tons over the original configuration. Pressure was on for the ship to leave for Karachi on 26th September to carry the Air Minister, Lord Thompson of Cardington. Although the target date was on course to be met, the wind was to keep the modified R.101 in the shed until the morning of 1st October.

“The New Ship”

It was at 06.30 on the 1st October that the R.101 emerged from the shed and was secured to the mast. The new ship had a more elongated look as she had been extended by 35 feet to insert the new bay.

At the same time, R100 was removed from Shed No 2, and walked in to shed No.1 where she too was to be altered in the same way to obtain more lift. It was the last time the outside world would see the R100.

The R.101 was moored serenely to her mast at Cardington and the crew were busy making preparations for a full 24 hour trial flight. A permit to fly had been issued and a full report on the new ship would be submitted later, a draft having been prepared. The permit to fly had been granted after a “good deal of general thinking”.

It was said by Professor Bairstow, who issued the permit, that “comparison on limited information has been required in reaching our conclusion”.

Final Trial Flight: 1st October 1929

The R.101 slipped her mast at 4.30 pm on 1st October to fly a 24-hour endurance flight to complete the engine and other trials. It was noted, however, and agreed by officers, Reginald Colemore, Director of Airship Development (DAD) and the AMSR, that if the ship behaved well and Major Herbert Scott, one of the most experienced airshipmen in the UK, was satisfied during his flight, then they could curtail the tests to less than 24 hours.

The ship left Cardington and headed south to London, then turned east following the Thames and out across Essex. She spent the night out over the North Sea. Those on board noted that the atmosphere was quiet and serene.

Due to the early failure of an engine cooler in the forward starboard engine, it was impossible for the ship to make a full-speed trial. During the flight, it was noted that conditions were “perfect” and all other items in the ship behaved perfectly.

Even though there was no time to make formal reports, it was noted that the ship handled, and she appeared to be much better in the air than before. It was agreed to curtail the flight and head for home at Cardington. The ship returned to the mast at 09.20 on Thursday, 2nd October; she had been in the air for just over 17 hours in smooth flying conditions.

Important things were needed by the crew following this flight. Captain Irwin had made special notice of all the concerns before the alterations. He noted that there was practically no movement in the outer cover; all sealing strips appeared to be secure; no leaks were observed in the gas valves; the movement of the gas bags was so slight that it was barely perceptible; and the padding was secure. All other items were found to be in good order, and he was satisfied with the independent inspection which had been carried out on the ship.

The senior members of the crew and technical office, along with the DAD, held a conference on Thursday evening and discussed whether to make the flight to India. It was noted that a longer trial, whereby full speed testing could be carried out in adverse conditions, was normally essential before such a long voyage.

It was also noted that a full speed trial was not recommended during the India flight due to the possibility of failure. At this stage, it had not been calculated what the state of the engines would be with the new design of the ship. Also, the risk of engine failure would mean putting the whole voyage in jeopardy, and hence it was deemed that cruising speed would be the maximum recommended speed for the journey.

Even though pressure had been put on all involved with the R.101 by the Air Minister suggesting that he must go to India and back in time for the Imperial Conference due on the 20th October 1930, there was one note on the 2nd October by Lord Thompson advising that

“You mustn’t allow my natural impatience or anxiety to start to influence you in any way. You must use your considered judgment.”

Final Flight – Saturday 4th October 1930

With the decision made that the India flight should take place, there were two further days of final preparation. The ship remained on the mast and the crews busied themselves in preparation for this momentous voyage. Of course, all staff were keeping an eye on the weather conditions to ensure that the ship would be able to make the voyage in the suggested time, not wanting to be inhibited by the problems all airships suffer with the natural elements.

Giblett, the meteorological officer, had been providing the officers with updates on the weather forecast over the last few days and the route was selected on his information.

Another weather conference was held on the morning of the 4th October and it was noted that the weather conditions over northern France were becoming cloudy with moderate winds. It was agreed that the ship would depart between 4pm and 8pm that evening.

Two further forecasts were issued to the ship during the day; these indicated that the weather conditions over Cardington and Northern France would begin to deteriorate during the evening, however, it was noted that the wind conditions would not increase significantly. These forecasts, even thought not particularly good, were not bad enough to cancel the voyage. The decision was made to hurry the passengers on board, complete the loading of the ship, and begin the trip in order to be passed the worst weather.

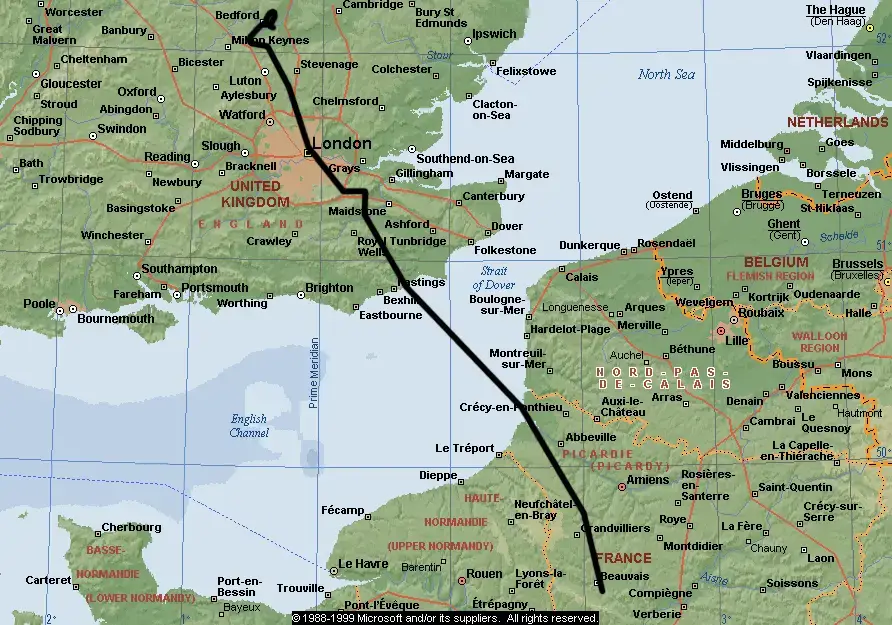

At 6.24pm R.101 left the Cardington mast in misty fine rain and darkness. The ship was illuminated by lights from the promenade deck and searchlights from the mooring mast.

As the ship was fully loaded with fuel to make it to the first stop, Egypt, it was noted that 4 tons of ballast had to be dropped before the ship gained height. The R.101 cruised passed the sheds and then headed west towards Bedford to salute her home town. She passed around the town and then headed south-east towards London. She was flying at her cruising height of 1,500 feet just below the cloud base and by 8pm R.101 was flying over London.

A wireless message from the ship was sent at 8.21pm:

Over London. All well. Moderate rain. Base of low clouds 1,500ft. Wind 240 degrees [west south west] 25mph. Course now set for Paris. Intend to proceed via Paris, Tours, Toulouse and Narbonne.”

An hour later R.101 was requesting the Meteorological Office at Cardington to wireless a forecast of the weather expected from Paris to Marseilles “with special reference to wind and cloud”.

A more severe forecast was issued at 2030 hrs as R.101 passed over London, showing a trough across northern France

At 9.47pm the following message was sent:

“At 21.35 GMT crossing coast in the vicinity of Hastings. It is raining hard and there is a strong South Westerly wind. Cloud base is at 1,500 feet . After a good getaway from the Mooring Tower at 18.30 hours ship circled Bedford before setting course. Course was set for London at 18.54. Engines running well at cruising speed giving 54.2 knots. Reached London at 2000 hours and then set course for Paris. Gradually increasing height so as to avoid high land. Ship is behaving well generally and we have already begun to recover water ballast.”

t was noted that with the loss of ballast at the beginning of the flight, the crew were more than confident that the water recovery system would replenish the supplies. The R.101 was fitted along the top of the envelope with catchment arrangements by which, when rain fell, water could be recovered to increase ballast and so compensate for the loss of weight arising from the consumption of fuel. It is noted that at this point the R.101 crew did not consider the ship to be heavy as original sources suggested.

The Channel crossing took two hours. At 11.36 pm the ship reported :

“Crossing French coast at Pointe de St Quentin. Wind 245 true. 35mph”

From 11.00 pm to 02.00 am the crew changed watches, R.101 continued on its usual watchkeeping status.

The 60-mile crossing was well known by Squadron Leader Johnson, who had flown the route many times between London and Paris. We can see that the wind speed was increasing at this time. It was estimated that at the time of crossing the channel, the R.101 was at a height of between 700 to 800 feet. It was later recorded that First Officer Atherstone took over the elevator wheel and ordered the coxswain not to go below 1,000ft.

At 00.18 the R.101 sent out the following wireless message:

“To Cardington from R.101.

2400GMT 15 miles SW of Abbeville speed 33 knots. Wind 243 degrees [West South West] 35 miles per hour. Altimeter height 1,500feet. Air temperature 51degrees Fahrenheit . Weather – intermittent rain. Cloud nimbus at 500 feet. After an excellent supper our distinguished passengers smoked a final cigar and having sighted thisFrench coast have now gone to bed to rest after the excitement of their leave-taking. All essential services are functioning satisfactorily. Crew have settled down to watch-keeping routine.”

This was the last message from the R.101 giving speed and position. The ship continued to send out directional wireless signals to check her position or to test the strength of the signals. The last directional signal addressed to Cardington was at 1.28 am. A final signal was sent from Cardington to the Croydon Station and relayed via ship at Le Bourget at 01.51 am. An acknowledgement at 01.52 am was the last signal ever sent by the R.101.

At 02.00 pm the watch changed as with normal routine on the ship, and still nothing was reported wrong with the ship. It can be assumed that had anything been noticed, the Captain would have had this signalled back to base. Also, if anything had been noticed, the Captain would not have allowed the men on duty to stand down and pass over to the new watch. Evidence of engineer Leech at the inquiry confirmed that Leech was off duty and enjoying a smoke in the smoking room between 01.00am and 02.00 am, when Captain Irwin came into the room and spoke to him and the Chief Engineer.

At 02.00 am, the ship reached Beauvais and passed to the east of the town. At this time, witnesses suggested that the ship was beginning to have difficulty with the gusting winds. Some suggested that the promenade lights became obscured, and early suggestions were made that the ship was rolling in the winds; however, no amount of rolling would explain the obscuring of the lights, and it seems more probable that intervening cloud was the cause.

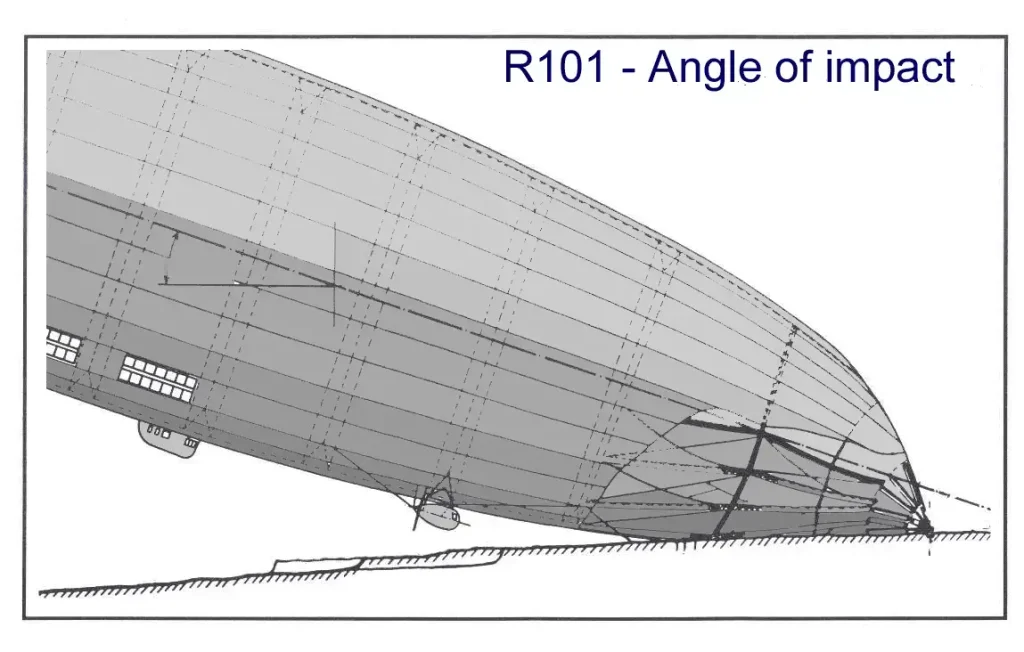

From survivor accounts, at 02.00 am the ship made a long and rather steep dive, sufficient to make the engineers lose balance and cause furniture in the smoking room to slide.

It is estimated that a rent occurred in the rain-soaked upper part of the nose, causing the forward gas bags to become exposed to the elements and damaged by the gusting wind. The loss of gas at this point could have led to the loss of control of the ship. Also, the ship was travelling towards the notorious Beauvais ridge, which was well known by aviators for its dangerous gusting wind.

The loss of gas at the forward part of the ship, combined with a sudden downward gust of wind, would have forced the nose down. Calculations by the University of Bristol in 1995 provided evidence that the maximum downward angle was 18 degrees in this first dive through a time span of 90 seconds.

The crew in the control car would have tried to correct the downward angle by pulling the elevator up. In the next 30 seconds, the ship pulled out of the forced dive and the crew were steadying the ship. Flying at a nose-up angle of three degrees enabled the ship to regain some aerodynamic stability. However, it was realised that the elevator was “hard up” and yet the crew knew that the nose was only three degrees above the horizon. This meant that the nose was now extremely heavy, and hence, a serious loss of gas from the forward bags must have occurred.

The Captain then rang the order for all engines to reduce speed from the original cruising speed, if not to stop them. The bells were heard and acted upon by the crew as evidence from the survivors.

Chief Coxswain George Hunt moved aft from the control car to the crew’s quarters. At this point, he passed crew member Disley and warned, “We’re down lads”. This famous comment by one of the most experienced airship crew members showed that the R.101 was not going to be able to continue and that an executive decision had been made to make an emergency landing

Just after this point, the ship moved into a second dive. It is calculated that R.101 was now at a height of about 530 feet, which for a vessel of 777 feet long was precarious.

Rapid oscillation of the ship had already occurred and any further oscillation would cause it to fail. Rigger Church was ordered to release the emergency ballast from the nose of the ship and was on his way to the mooring platform when he felt the angle of the ship begin to dip once more from an even keel.

Captain Irwin made no remarks about the ship except that the after engine continued to run well. Chief Engineer Gent later turned in, and Leech went and inspected all the engine cars. He found them all to be running well and returned to the smoking room.

Recent research by Dr Brian Lawton, whose research paper can be found here, updates the notion of a second gust of wind causing the nose to drop, whereby his research states that a control cable snapped, and despite the tail elevator being hard-wound in the up position, the elevator itself failed to respond. Dr Lawton’s research is now being seen as the most accurate conclusion as to why the R.101 was unable to recover from the dive fully.

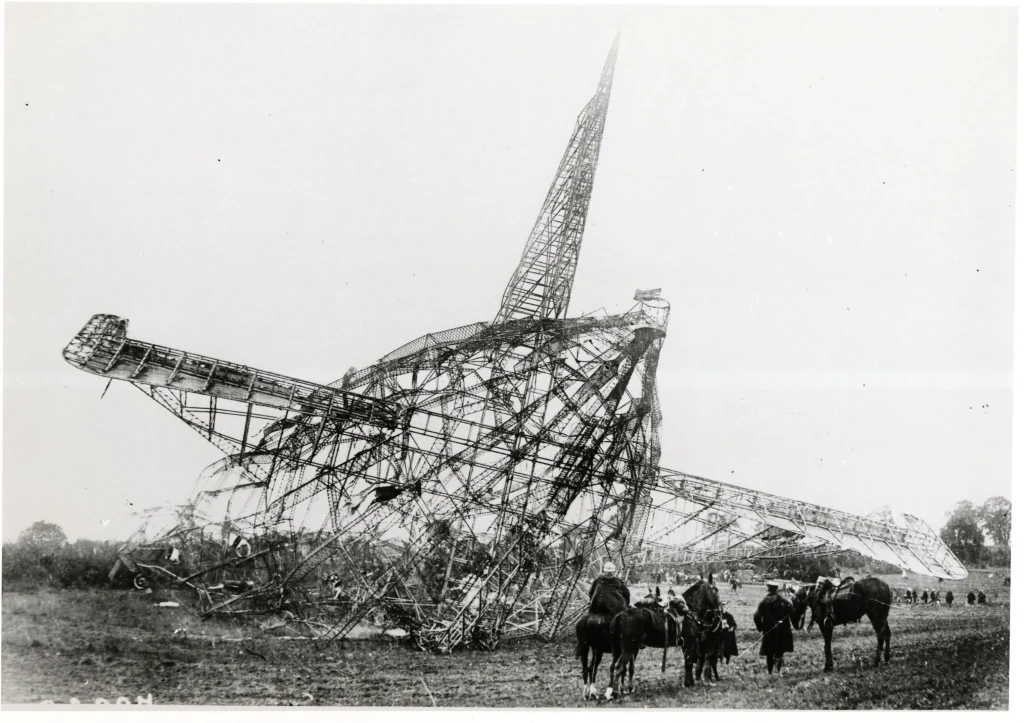

The ship began to drop again through a downward angle, and at this point, the nose hit the ground. Evidence from the official inquiry noted that the R.101’s ground speed had reduced to almost that of a perfect landing. The impact of R.101 with the ground was very gentle, and it was noted that the forward speed of the ship was only 13.8 mph. The ship bounced slightly,moving forward some 60 feet, and then settled down to the ground.

The survivors recall that a “crunch” was heard and the ship levelled. There was no violent jarring from the impact.

Evidence from the crash site confirmed this as the only impact mark in the ground was a two-foot deep by nine-foot long groove which was cut by the nose cone, in which soil was later found. Also, the starboard forward engine had struck the ground whilst the propeller was still revolving, and grooves were made by this. The engine car had been twisted completely around on its struts.

After the impact, fire broke out. The most probable cause of this was that the starboard engine car was twisted around, and the hot engine had come into contact with the free gas from the rents in the forward gas bags. The fire immediately consumed the ship, causing each gasbag from the forward to after part of the ship to explode.

The force of the explosions was noted by the position of the gas valves and the damage to the framework of the ship. The outer cover was immediately consumed in the ensuing inferno.

Of the crew and passengers, only 7 men were able to escape from the wreck.

- Foreman Engineer J H Leech was sitting in the smoking room at the time of the impact and was saved by the accommodation bulkhead collapsing from above and being held by the top of the settee in the smoking room. He was able to escape through the side of the damaged wooden walls of the smoking room, out through the framework and through the cloth outer cover of the ship to safety.

- Engineers A V Bell, J H Binks, A J Cook, and V Savory were in their respective engine cars, which were positioned outside the main hull. When the ship landed, they were able to escape through the windows of the engine cars and run away from the ship.

- Wireless Operator A Disley, who was asleep in the crew’s quarters, was awakened when his bunk, which was aligned in the same forward direction as the ship, assumed the curious angle of the first dive. He felt the ship come out of that dive to an even keel and then to a nose-up angle. At the same moment, Hunt passed through the crew’s quarters and advised them of the situation.

At this point, Disley heard the telegraph ring out in the ship. The electrical switchboard was close at hand, and he started to get out of his bunk to cut off the electric current to the ship, as he knew that in any aircraft crash, there may be a chance of fire. There were two field switches, and he recalls tripping on one of them. During this action, the ship went into its second dive,e and he was just about to cut the second switch when the impact was heard and the lights went out all over the ship. Disley recalls that the impact was so gentle that it was not enough to unbalance him from his feet. Seconds later, like Leech, he was fighting his way through the wreckage to the outside of the ship.

- The last survivor was Rigger Church, who later died of his injuries three days after the crash. He was interviewed and gave the following statement.

“I would consider the flight rather bumpy, but not exceptionally so. The second watch had just come on and I was walking back when the ship took up a steep diving attitude. At this moment I received an order to release the emergency forward water ballast [1/2 ton in the nose] but before I could get there the crash came.“

The emergency ballast was in the very nose of the ship. It could not be released from the control car and had to be jettisoned locally.

The R.101 came to rest with the forward part of her nose in a wood of small trees and the rest of her hull in a meadow. When getting away from the ship, both Disley and Cook made some valuable observations. Disley noted that even though the outer cover was burning, there was almost no cover left on the top of the ship aft of frames 10 and 11; the ship appeared to be a skeleton. Cook noticed that the underside of the elevator still had its outer cover and was positioned in a full up position, suggesting that the coxswain was still trying to keep the nose up on landing. The inquiry noted that the number of turns on the auxiliary winch drum confirmed this.

The Aftermath

The survivors were treated in the local hospital, and the inquiry began the following morning, with the French authorities surveying the site and condition of the wreck whilst the British investigators were flown in. Messages were wired to England in the early hours of the morning, reporting the crash to a stunned British public.

Rigger Church died in the hospital from his injuries and joined the other victims of the crash. Full state honours were given to the victims and special trains were laid on to transport them from the crash site to the channel. H.M.S. Tempest carried them from Boulogne to Dover, where a special train took the bodies to Victoria Station. From there, they were carried in state to Westminster Hall at the Palace of Westminster and were laid in state. The mourning public waited many hours to pay their respects by filing past the coffins. A memorial service was held at St Paul’s Cathedral on Saturday, 11th October, after which the coffins were taken by train to Bedford.

They were then transferred to lorries and walked the two miles to Cardington Village, where a space had been prepared in the churchyard.

All 48 dead were finally laid to rest in a special grave. A final small service was undertaken, with distinguished guests including Hugo Eckener and Hans Von Schiller, followed by a flypast by the RAF flight.

In 1931, a memorial tomb was completed and inscribed with the names of the victims. This memorial still dominates the tiny churchyard to this day.

The Wreckage

The wreck of the R.101 lay where it had fallen until well into 1931, becoming a haunt for air accident investigators and day trippers who wanted to see the near-perfect skeleton of the largest airship in the world. Thomas William Ward, scrap metal contractors from Sheffield who were specialists in stainless steel, were employed to salvage what they could.

It was noted in the records of the Zeppelin company that they purchased 5,000 kg of duraluminium from the wreckage for their own use. Whether this was for testing and analysis or to recast and use in the “Hindenburg”, is open to further research and speculation.

The Survivors

HARRY LEECH

Foreman Engineer Henry James Leech was one of the survivors of the R.101 crash and was awarded The Albert Medal for his bravery in rescuing Arthur Disley (wireless operator) from the burning wreckage of the airship despite suffering serious burns himself. He was presented with this medal by King George in 1931. He was already the holder of an Air Force Medal for gallantry gained in WWI. Harry lived in Shortstown from 1925-1930. He was also an engineer together with Leo Villa for Sir Malcolm Campbell and his son Donald during their World Speed Records. Harry himself was partially blinded when returning from Coniston in a car driven by Lady Campbell which crashed.

He was a brilliant engineer and worked at the University of Southampton, and later at the South Hants Hospital where he also helped develop and build a ‘Caesium Unit for the treatment of malignant disease in the late 1950’s.’

Harry Leech died aged 77 in November 1967

VICTOR SAVORY

There is very little known of what happened to Victor Savory, but thanks to his relative John Millman, we know that his real name was Alfred Victor Alexander Savory, and John remembers him as a “lovely man – 6ft 4ins tall and of heavy build.” He began his career as an Engineer in the Royal Air Force and was badly burned in the R.101 crash. In WW2, Victor worked as an AID (Air Inspectorate Division) Inspector at the A V Roe Company (AVRO) in Lincoln.

In John’s words again – “Occasionally he would visit us for a couple of days and mother (Gertrude Savory n. Millman) would always put herself out for him, he was her favourite brother”.

Thanks to research by Mike Strange, he has tracked down these additional details:

Born 22nd July, 1897 in London.

His birth was registered in the 2nd quarter of 1897 in the Hackney Registration District

He had been a member of the Great Britain, Royal Aero Club Aviators, with his profession stated on the club membership card dated 27th February 1935 as “Garage Proprietor”. At the time of his Aero Club membership, he was living at 14 Malood Road, Balham, London

He died on 8th October 1970 with his address as 60 and a half, Bailgate, Lincoln.

JOHN HENRY ‘JOE’ BINKS

Engineer John Henry Binks (more commonly known as Joe) was born on 29.12.1891. John Henry served in the Navy for 12 years and joined the crew in 1929 and by 1930 was a resident of Shortstown. In 1933, it was reported in the local press that he had fainted at the first R.101 memorial service held at Allone in France.

He continued to work on the camp for many years after and was part of the small team who worked on Lord Ventry’s airship, The Bournemouth, in the early 1950’s. Binks Court in Shortstown is named after him in a tribute to his long association with the area. We don’t have details of when or where he died.

ARTHUR BELL

Survivor Engineer Arthur Victor Bell first arrived in Shortstown in 1927 and his son Bill was born here in 1929. He had joined the Airship Service back in 1919 and was also on the R33 when it broke away. Arthur remained In Shortstown for many years and played a very active role in village life. However we don’t have his death date or location.

ARTHUR DISLEY

Wireless Operator Arthur Disley was one of a few men who served on both the R100 and R.101 airships and indeed was part of the crew on the R100 flight to Canada. According to the R100 pre-flight press release, he joined the RNAS on 04.03.1920.

He was stationed in Shortstown from 1930-1931. When the R.101 fell to the ground, Arthur Disley was able to escape; however, his hands were badly burned, but he showed great fortitude and insisted on relaying the news back home before allowing himself to be medically treated. For this act of selflessness, he was awarded an Order of The British Empire medal. We don’t have any details of his further career or details of his death.

ARTHUR COOK

The details we have obtained from his daugher on his further carrer. During WW2 he was ranked a Lieutenant in the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm reserves. After the war he continued working for the Air Ministry in aircraft maintenance, at RAF Wroughton, Wiltshire. He moved up to Wellington in Shropshire again for a RAF station. In 1951 he moved to Gloucestershire when he was posted to RAF Aston Downs and when that closed RAF Kemble where the Red Arrows were first formed.

In January 1958, he was awarded the MBE by Queen Elizabeth for his services to the Air Ministry.

He retired as a Senior Technical Superintendent – Royal Air Force in the late 60’s and bought a guest house in Sidmouth before retiring to Alicante in Spain. He returned to the UK in the 80’s again to Gloucestershire and died aged 91 on the 7th November 1998

Flight Log of H.M.A. R.101

| Flight Log of H.M.A. R.101 | |||||||

| Flight no. | Date | Departure | Arrival | Duration | Miles | Route | Details from records made by Ernie Watkins, R101 Engineer, personal Log and Sir Peter Masefield’s “To Ride the Storm” |

| 1 | 14th Oct 1929 | 11.17 am | 16.57am | 5h 38min | 108 | Cardington -London return | Cardington – Bedford – Leighton Buzzard – Luton – St Albans London (West End) – City of London – St Albans – Harpenden – Luton – Cardington |

| 2 | 18th Oct 1929 | 08.12am | 17.50pm | 9hr 38min | 210 | Cardington – Midlands return | Cardington – Bedford – Northampton – Rugby – Daventy – Coventry – Birmingham – West Browwich – Derby – Nottingham – Newark on Trent – Leicester – Wellingborough -Bedford – Cardington |

| 3 | 1st Nov 1929 | 09.40am | 16.55pm | 7hr 15min | 260 | Cardinton – Norfolk return | Cardington – Bedford – Wisbeech – Sandringham – Kings Lynn – Cromer – The Wash – Out to Sea – Kings Lynn – Norwich – Pulham – Bury St Edmonds – Newmarket – Cambridge – St Neots – Cardington. |

| 4 | 2nd Nov 1929 | 20.12pm | ¬ | . | . | Cardington – | Cardington – Bedfod – Luton – St Albans – London – Croydon – Farnham – Portsmouth – Southampton – Isle of Wight – The Needles – Southampton – Basingstoke – Reading – Tring – Bedford – Cardington |

| 3rd Nov 1929 | . | 10.14am | 14hr 2min | 380 | South England return | ||

| 5 | 8th Nov 1929 | 13.47pm | 16.51pm | 3hr 4min | 52 | Cardington -Local Bedford return | Cardington – Bedford – Wellingborough – Kettering – Cambridge – St Neots – Cardington |

| 6 | 14th Nov 1929 | 13.34pm | 16.43pm | 3hr 9min | 62 | Cardington -Local Bedford return | Cardington – Henlow – Hitchin – Welwyn – Hatfield – Welwyn – Hitchin – Henlow – Cardington |

| 7 | 17th Nov 1929 | 10.33am | ¬ | . | . | Cardington – Scotland- Ireland | Cardington – Bedford – Lincoln – York – Howden – Durham – Newcastle – Berwick – Dunbar – Edinburgh – Falkirk – Glasgow – Belfast – Isle of Man – Blackpool – Dublin – Bray – Holyhead – Anglesey – Llandudno – Chester – Licthfield – Cardington |

| 18th Nov 1929 | . | 17.14pm | 30hr 41min | 1,148 | Midlands – Cardington | ||

| 30th Nov 1929 – 23rd June 1930 | In Shed for Winter | (Altering of gas bag wiring) | . | . | . | ||

| 8 | 26th Jun 1930 | 15.51 pm | 20.26pm | 4hr 35 min | 217 | Cardington – Test Flight return | |

| 9 | 27th Jun 1930 | 07.22am | 19.50pm | 12hr 33min | 461 | Cardington – London (Hendon) return | |

| 10 | 28th Jun 1930 | 07.25am | 19.51pm | 12hr 26min | 435 | Cardington – RAF Hendon Display-return | |

| 29th Jun 1930 – 1st Oct 1930 | In shed | (Fitting of extra bay) | . | . | . | ||

| 11 | 1st Oct 1930 | 15.36pm | . | . | . | Cardington – East of England- | |

| 2nd Oct 1930 | . | 08.27am | 16hr 51min | 637 | North Sea – Cardington Return | ||

| 12 | 4th Oct 1930 | 18.36pm | 02.09am. | 7hr 33min | 248 | Cardington-Crash at Beauvais,France | Cardington – Bedford – Luton – Kimpton -Bendish – Hatfield – Alexandra Palace – London – Shadwell – Greenwich – Sidcup – Bodium Castle – Hastings – Pointe de St Quentin – Verigies – North of Blicourt – Beauvais- Bios de Coutumes – Allonne |

| Total | 127h 20min (5.3 days) | 4,218 | Total Passengers 186 | ||||

We have also documented the R.100 and R.101 times taken to moor and move the ships when on the Cardington mast